19.7.–12.8.2012

Domènec

The Worker’s Hand

The exhibition The Worker’s Hand (Rakentajan käsi), which opens at Cable Gallery on July 19, presents Spanish artist Domènec’s (b. 1962) new installation, which seeks to revisit the forgotten history of Kulttuuritalo (The House of Culture) designed by Alvar Aalto and built in 1952–58 in what was then the working class district of Kallio in Helsinki. The installation is the result of Domènec’s collaborative research with Helsinki-based Spanish curator Jon Irigoyen (b. 1978). The project was devised and carried out during Domènec’s artist residency at HIAP Suomenlinna in autumn 2011 and summer 2012.

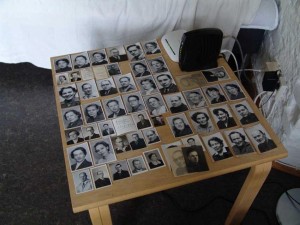

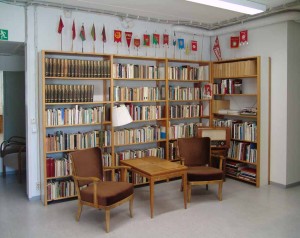

Kulttuuritalo, a cultural complex housing a concert hall, offices, a theatre and a library, was commissioned by the SKP (Communist Party of Finland), and largely built by volunteers. The exhibition focuses on the volunteer workers, trade unionists and families who responded to the SKP’s call to build a “house for all workers” and gave more than 500,000 hours of their lives to the realisation of the project.

Revisiting the history of the construction of Kulttuuritalo, Domènec and Irigoyen’s project aims to recover the memories of the numerous militant workers and volunteers who participated in the collective construction of this symbol of modernism and icon of the Finnish labour movement. At the same time, the exhibition addresses the historical gap between the era when Kulttuuritalo was commissioned by the SKP, and the present moment, when the building has been transformed into an architectural monument stripped of its ideological ‘baggage’. This attempt to revisit the past prompts reflections on the collapse of the modern project and on the way we experience historical time.

Domènec’s artistic practice focuses on the debate that raged, since the 1960s, about the historical process called ‘the crisis of modernity’. In a deliberate expansion of the field of sculpture, Domènec has developed a universe of his own, which reflects the decline in the social visibility of the great modern narratives. In his works Domènec extols the metonymic power of modern architecture and provides a platform for a critical re-reading of the utopian aspect of modernity.

Jon Irigoyen is an independent curator and artist born in Bilbao, Spain, and currently based in Helsinki. He was a founding member of the experimental contemporary dance collective Liikë in Barcelona. Since 2009, he has been on the Board of Helsinki’s Pixelache Festival. His research interests and projects span the intersecting relationships between artist and spectator; the interaction between public and urban space; the perception of reality; as well as concepts such as autonomy, resistance and memory. Irigoyen has devised and implemented projects, exhibitions and workshops in Finland, Spain, Ireland, Lithuania, Latvia, Colombia, Russia and elsewhere.

Thanks to:

Can Xalant Center for Creation and Contemporary Knowledge of Mataró, Institut Ramon Llull, CoNCA, Spanish Embassy in Finland, Pixelache Festival,

Pirjo Kaihovaara, Tiina Rajala, José M. Sánchez (Kinetic Pixel), The Association of Pensioners (Eläkeläiset ry), Ernest Borras, Berta Julivert.

Special thanks:

Kansan Arkisto and the Kulttuuritalo volunteers: Eine Kauppila, Osmo Halenius, Kerttu Laine, Antero Koski, Matti Lääperi, Toivo Lindroos, Elbe Novitsky, Irja Pesonen, Sisko Salonen, Petteri Sosoi, Riitta Suhonen, Tapio Rajala, Veijo Sinisalo.